by Dadewethu Fika

Following the Supreme Court of Appeal’s decision in November 2020 to declare the Preferential Procurement Regulations of 2017 concerning supply chain management (SCM) as invalid, rules which allowed organs of state to implement pre-set criteria around the types of suppliers with whom the government would do business (which would ordinarily imply that others could be excluded from consideration), this appeared to be as good an opportunity as any to revisit past “controversies” around government spending and its link to that all-important selection criteria: broad-based black economic empowerment. This is especially applicable because the educating of those opposing this “progressive” government policy appears to be really lacking by the media and those in government – the people one would ordinarily expect to have the know-how – which is as disappointing as the lack of pushback from any quarters including those who have been empowered through having delivered goods and/or services for the government.

Background

The framework for SCM which is also referred to as procurement management is entrenched in section 217(1) of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 which states, “When an organ of state in the national, provincial or local sphere of government, or any other institution identified in national legislation, contracts for goods or services, it must do so in accordance with a system which is fair, equitable, transparent, competitive and cost-effective.”

Subsection (2) continues to say that subsection (1) does not prevent government from having policies in place which allow for preferences in the allocation of government contracts, and protects or advances people disadvantaged by unfair discrimination. Subsection (3) then gave effect to the nationally-legislated basis of preference and attempts at redress through the development of the Preferential Procurement Policy Framework Act, 2000 (PPPFA) in the awarding of government contracts to prospective suppliers, with the minimum threshold-value for which this law would apply being dependent on the type of government organisation seeking to make such an award.

Application of the law

To assist with the principles of preferential treatment in the making of government contracts, the PPPFA introduced a points-scoring system for the evaluation of bids submitted by prospective suppliers, as contained in regulations 5 and 6 of the Preferential Procurement Regulations, 2011. In those two regulations are the following formulae which form part of “the 80/20 preference point system” and “the 90/10 preference point system” respectively:

Ps = 80 * (1 – [{Pt – Pmin} / Pmin]) OR Ps = 90 * (1 – [{Pt – Pmin} / Pmin]),

Where Ps is the number of points out of 80 or 90 to be awarded to each bid, Pt is the price of the bid and Pmin is the lowest price offered out of all bids accepted.

So, the score out of 80 or 90 given to each bid received from bidders (read interchangeably with “tenderers”) is based on the percentage of the price of that bid to the lowest-priced bid, i.e. the lowest-priced bid will be scored the maximum number of points available.

The remaining 20 or 10 points are then scored to bidders on a sliding scale, depending on their “B-BBEE status level of contributor” as follows:

The 80/20 preference point system: Level 1 = 20 points, 2 = 18, 3 = 16, 4 = 12, 5 = 8, 6 = 6, 7 = 4, 8 = 2 or “Non-compliant contributor” = 0

OR

The 90/10 preference point system: Level 1 = 10 points, 2 = 9, 3 = 8, 4 = 5, 5 = 4, 6 = 3, 7 = 2, 8 = 1 or “Non-compliant contributor” = 0

The effect of all of this is that the bidder with the highest combined score would in theory be awarded the contract.

And so we arrive at one of the key points of misinformation: 1) B-BBEE plays an insignificant part in the determination of the awards to be made. Easily, the bigger contributing factor is a tenderer’s relative pricing for the goods and/or services being tendered for. This means that it is probable that B-BBEE tenderers are effectively “priced-out” of a government contract through not having quoted a price close enough to their generally more experienced, better resourced non-B-BBEE counterparts, even before the remaining scores for B-BBEE levels come into consideration. It is further submitted that because their businesses should be better run and more sustainable due to relative strength of experience and business acumen, this allows the non-B-BBEE counterparts to be “loss-leaders”, in that they could price their offered goods and/or services at even lower margins (than they otherwise would) in order to establish ties with the government with future contracts in mind, a luxury which could reasonably not be afforded by B-BBEE tenderers.

But of course, non-B-BBEE bidders have adapted somewhat and have entered into legal partnerships (at their best) and “fronting arrangements” (at their worst), which allow these joint tenderers to score points as tenderers who have attained a certain B-BBEE status level of the contributor. This leads us to a second key point of misinformation: 2) Non-B-BBEE bidders are also able to score B-BBEE points through partnering up with historically disadvantaged persons. This development which has been going on for a number of years further narrows the “wiggle-room” available for B-BBEE bidders regarding how close their tendered prices have to the other prices submitted, as can be seen below:

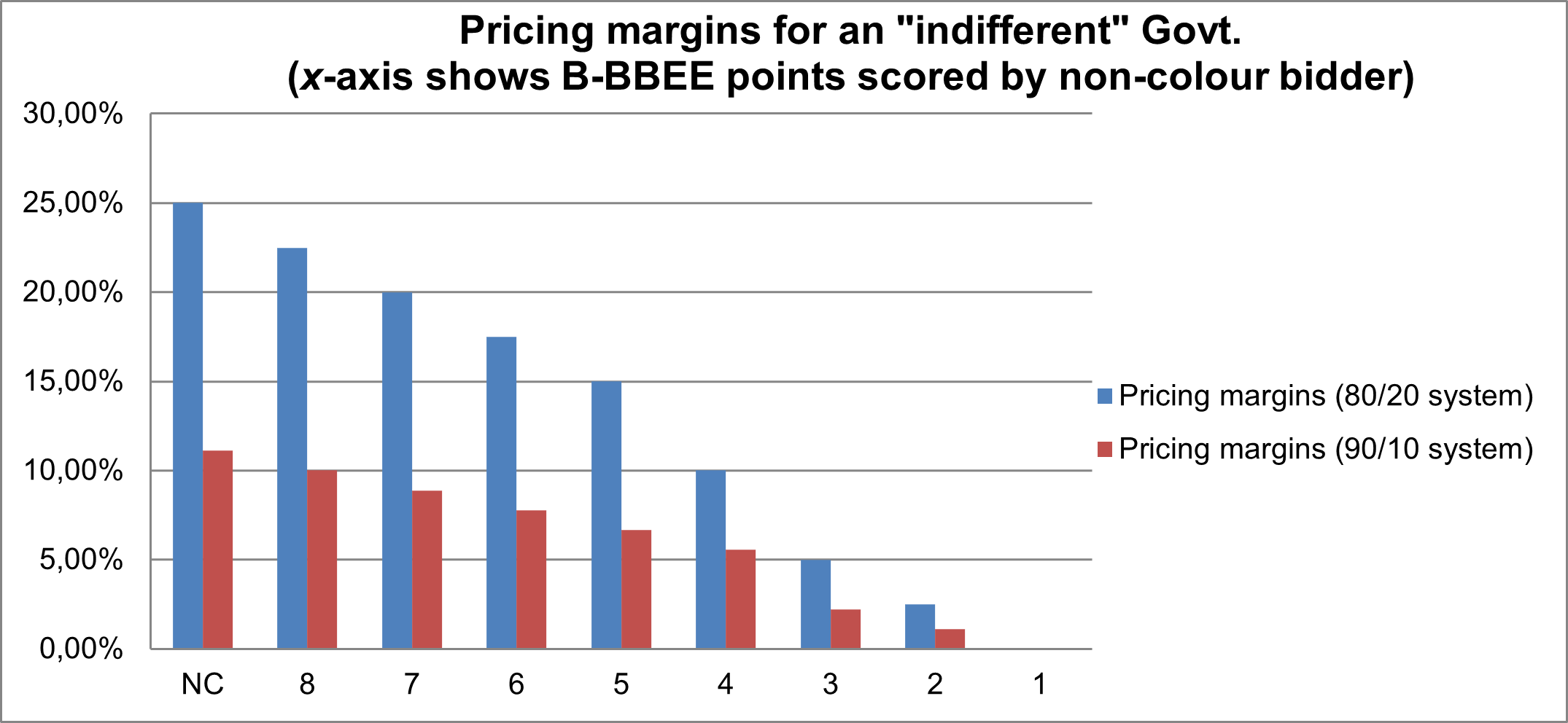

Assume that there are only two prospective suppliers, with the supplier of colour always scoring the full B-BBEE points and the supplier of “non-colour” always offering the lower price. If the only variable changed at a time is the number of B-BBEE points the non-colour supplier can score, we see the following regarding the maximum price-gap possible between the two in order for the government to be “indifferent” concerning who wins the contract:

From the above, it can be easily seen that there is a smaller margin for error in terms of the possible prices which can be offered by the supplier of colour, the more points his counterpart can possibly score as a B-BBEE status level of the contributor. This is especially true for those awards which fall into the 90/10 preference point system (where the size of these contracts is bigger in value for the required goods and/or services), which basically forces the supplier of colour to be pricing their products within the 90th percentile for him to be competitive and stand a chance of winning the bid.

This would be akin to a teacher requiring a student of colour to score above the 90th percentile in order for them to do something significant and of worth, possibly even life-changing, for the school and for themselves. It is submitted that this is a preposterously high standard, which may not ordinarily be met by the historically disadvantaged student! This would essentially mean that these projects would always be carried out by the non-colour student, which in turn does nothing for the “fair treatment” of the student of colour, no matter how much the selection process treated them as “equals” in competition with one another.

It is hoped that this aspect will be revisited in later editions, namely the question concerning whether the school (read “society at large”) was obligated to its students of colour in terms of properly capacitating them for the future.

Problem statement

Amongst many other flaws in this South African government policies, a case has to be made that it is virtually impossible for legislation (and by extension, its government and vice-versa) to treat its citizens both fairly and equitably simultaneously unless said people were always treated the same i.e. “equally” from the very beginning. Failing that crucial prerequisite, which is true not just for the Rainbow Nation but for a huge part of the world, the ideals of fairness and equitability cannot co-exist but have to be considered mutually exclusive, in that the pursuit of the one would automatically mean the forgoing of the other.

Without making this a philosophical debate but these immutable principles surely underlie true social justice, all the more so for legislation that is burdened with the task of being fair, equitable, competitive and preferential, all at the same time. It is hoped that the champions of equality and/or those celebrating the x number of years since democracy/freedom would stop and honestly consider if the proverbial pressing of the reset button actually is possible if society was not to commit itself in earnest to going back to the beginning to ensure that the fair treatment of its citizens is achieved.